Bizarre British Social Classes That (Thankfully) No Longer Exist

- Jennifer Still

- June 12, 2025

The Headington Magazine, 1871, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Headington Magazine, 1871, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsBritain’s social hierarchy has always had its oddities, but history reveals some truly bizarre categories of people who once had very specific, and often absurd, places in society. Some were official, others informal. Either way, these groups are long gone now, and probably for the best. Here’s a look at the strangest British social classes that once existed, what they were for, and why they disappeared.

Gong farmers

In Tudor and Elizabethan England, gong farmers were responsible for one of the worst jobs imaginable: digging out human waste from cesspits and privies. The word “gong” came from the Old English gang, meaning “to go.” So a gong farmer was literally someone who dealt with where people had gone.

Because of the appalling stench and health risks, gong farmers were only allowed to work at night and had to live on the outskirts of towns. Despite the nature of the job, it was surprisingly well-paid, as no one else wanted to do it. The job faded out in the 19th century as proper sewage systems were introduced.

Sin-eaters

In parts of Wales and the English border counties, a profession known as the sin-eater existed well into the 18th century. These people were paid to consume bread and ale placed on the chest of a deceased person, symbolically taking on their sins, so the dead could pass into the afterlife cleansed.

It was a mix of folk religion and desperation, and the people who performed the role were usually poor and socially isolated. They were both feared and pitied—necessary but tainted. As Church doctrine became more dominant and social welfare improved, the need for sin-eaters declined.

Clapperdudgeons

This class of professional beggars emerged in the Tudor period, when vagrancy laws divided the poor into “deserving” and “undeserving” categories. Clapperdudgeons faked injury or illness, often applying fake sores or using crutches, to get alms from the public.

They were often part of organised begging rings and were seen as nuisances by authorities. There were even guidebooks written to help the wealthy spot and avoid them. By the 19th century, with the rise of workhouses and formalised welfare systems, this kind of role disappeared.

Knocker-uppers

Before alarm clocks became widespread, people in industrial towns hired “knocker-uppers” to wake them up for work. These human alarm clocks used long sticks, pebbles, or even pea-shooters to knock on bedroom windows. Some worked entire neighbourhoods.

It was a recognised job well into the early 20th century, especially in places like Lancashire and East London. Knocker-uppers were usually older men or women who worked odd hours. As mechanical alarm clocks became affordable and reliable, the job faded away.

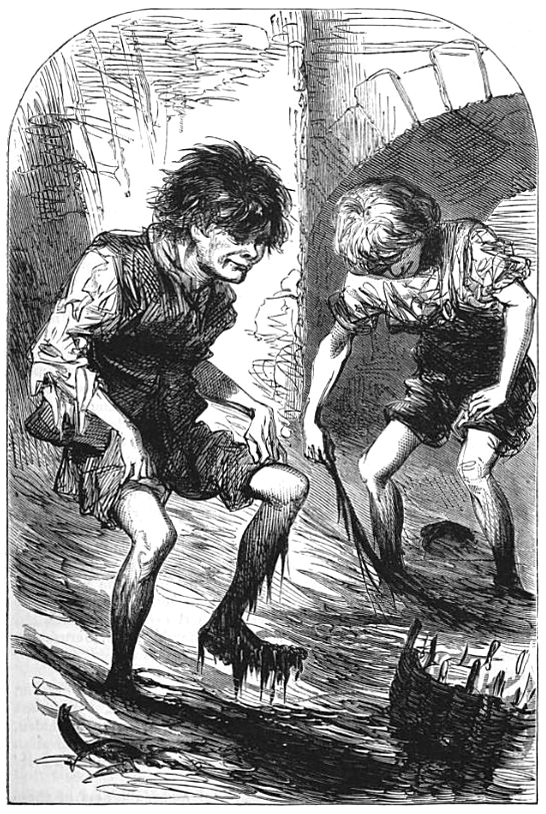

Mudlarks

In 18th- and 19th-century London, mudlarks were people, often children, who scavenged along the banks of the Thames at low tide, looking for coal, rope, bones, or metal to sell. The job was filthy, exhausting, and dangerous. Mudlarks had to dodge tides, sewage, and sometimes even corpses.

Though never officially a “class,” mudlarks were part of a recognisable underclass in London. They had their own territory and unwritten rules. Today, modern mudlarking is a hobby (and subject to regulation), but the original mudlarks lived a life of hardship that’s hard to imagine now.

Link-boys

Before streetlights, wealthy people often hired link-boys—young lads carrying flaming torches—to guide them through dark city streets. It was common in the 17th and 18th centuries in London. Link-boys were usually very poor and vulnerable to exploitation.

While some were trustworthy, others were known to lead clients into alleyways to be robbed. The job disappeared with the arrival of gas lighting in the 19th century. But for a while, link-boys were an eerie and ever-present part of city life.

Resurrectionists

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, medical schools needed cadavers for dissection, but legal sources were limited. That created a niche role: resurrectionists, or body snatchers. These people dug up freshly buried corpses and sold them to anatomy schools.

While technically not murderers, they were despised by the public and worked in secret. The trade became so common that some families guarded graves or used iron cages called mortsafes. The Anatomy Act of 1832 finally made legal provision for body donation, ending the trade.

Dog whippers

During church services in the 16th and 17th centuries, it wasn’t uncommon for dogs to follow their owners into the pews—or just wander in. To deal with the inevitable barking, chasing, or fighting, some churches hired dog whippers.

These men carried long sticks or whips and were tasked with removing dogs from the church quietly. Some even had official uniforms. As societal norms changed and dogs were no longer permitted in churches, the job became obsolete.

Ale-conners

Dating back to medieval times, ale-conners were tasked with tasting and testing the quality of ale and beer sold in towns and markets. They ensured it wasn’t watered down, too weak, or contaminated. It was an important role at a time when beer was safer to drink than water.

To test the strength, some conners reportedly sat in leather breeches soaked in beer to see if it was sticky—if they stuck to the seat, it meant too much sugar had been added. The position became ceremonial by the 18th century and has all but disappeared today, though some towns still appoint honorary ale-conners for tradition’s sake.

Britain’s past is filled with forgotten jobs and social roles that now seem odd or even grim.

Many existed because of poverty, poor infrastructure, or religious superstition. Their disappearance isn’t just a sign of progress. It’s a reminder of how much hardship and inventiveness shaped daily life in earlier centuries.