Historical ‘Wizards’ Who Were Actually Brilliant Scientists

- Gail Stewart

- May 2, 2025

Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphotoThroughout history, people with an extraordinary understanding of the natural world have often been called things like “sorcerer,” “magician,” or “wizard.” In reality, many of these so-called mystics were early scientists, using observation, experimentation, and logic in a time when such approaches were misunderstood, feared, or outright condemned. Many of them lived in eras when religious dogma or superstition dominated, and the very act of questioning established truths could land you in trouble—or worse. Here are 10 historical figures once thought to be wizards, but who were actually brilliant scientists far ahead of their time.

1. Roger Bacon (c. 1219–1292)

A 13th-century English philosopher and Franciscan friar, Roger Bacon was often referred to as “Doctor Mirabilis”—the wonderful teacher. He was one of the earliest European advocates of the scientific method and believed that knowledge should be built through direct experience and systematic experimentation.

Bacon’s writings touched on alchemy, astronomy, mathematics, and optics. He described the construction of eyeglasses, speculated on flying machines, and even theorised about telescopes centuries before they were invented. His reputation for magical knowledge came partly from his experiments with lenses and light, which were so unusual at the time they seemed supernatural. Many clerics were suspicious of his ideas, and Bacon was briefly imprisoned by church authorities. Despite that, his work laid important groundwork for future scientific thought.

2. John Dee (1527–1609)

John Dee, adviser to Queen Elizabeth I, was a brilliant mathematician, astronomer, and navigator who also immersed himself in the occult. He believed science and magic could be harmonised and used them together to understand the universe. Dee was also a key figure in the advancement of early British imperial policy and cartography.

His scientific achievements include refining navigational instruments and coining the term “British Empire.” However, he also believed in communicating with angels through a scrying mirror and spent years transcribing what he believed were divine messages. While modern scholars view Dee as a complex blend of scientist and mystic, in his day, many thought he was a sorcerer. His home was ransacked during political unrest, and he died largely discredited. Still, his contributions to navigation and astronomy had long-lasting influence.

3. Paracelsus (1493–1541)

Paracelsus was a Swiss physician, alchemist, and philosopher who fundamentally changed the way medicine was practised. He challenged the prevailing view of medicine based on the ancient Greek theory of four humours and introduced the use of chemical substances in treatment. He argued that illness came from external agents and not internal imbalances.

Though he embraced some mystical language and imagery, Paracelsus conducted real experiments and was particularly skilled in practical medicine. His ideas about dosage—”the dose makes the poison”—laid the foundation for toxicology. Despite his innovative approach, his rejection of established authorities earned him enemies, and his reputation as a magician persisted for generations.

4. Giambattista della Porta (1535–1615)

Della Porta was an Italian scholar and author of Magia Naturalis (Natural Magic), a book that combined recipes, experiments, and theories on subjects ranging from agriculture to optics. He experimented with lenses, mirrors, and what would later become the principles behind the camera obscura.

He also had an interest in cryptography and attempted to develop secret codes and languages, contributing to early forms of communication security. Because his interests spanned everything from horticulture to magnetism to the human face’s relation to personality, his eclectic pursuits were often viewed with suspicion. His scientific society was shut down by the Inquisition, who feared his studies bordered on heresy. Nonetheless, della Porta influenced Renaissance thinkers and played a role in the transition from magical thinking to empirical investigation.

5. Ramon Llull (c. 1232–1316)

A philosopher, theologian, and logician from Majorca, Ramon Llull created one of the earliest models for combining logic with theology. He aimed to convert Muslims and Jews to Christianity by reasoning rather than violence, and in doing so, developed mechanical devices with rotating wheels to generate combinations of concepts—effectively a primitive computational model.

His vision of a universal logical system anticipated some of the goals of modern computing and artificial intelligence. Because he spoke in complex symbolic diagrams and mystical-sounding language, later generations misunderstood his work. Yet Llull’s combination of reason, faith, and logic was extraordinarily advanced for his time.

6. Michael Scot (c. 1175–c. 1232)

Michael Scot was a Scottish scholar, astrologer, and mathematician who translated key Arabic texts into Latin, making the works of Aristotle and Avicenna accessible to medieval Europe. He worked at the court of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, where his skills in astronomy and medicine made him invaluable.

Despite this, tales about Scot conjuring demons or turning people to stone spread throughout Europe. Dante even placed him in hell in The Divine Comedy, and later authors portrayed him as a powerful necromancer. In truth, Scot was a deeply knowledgeable translator and scientist who played a vital role in reviving classical knowledge during the Middle Ages.

7. Jabir ibn Hayyan (c. 721–c. 815)

Jabir, known in Latin as Geber, is considered the father of chemistry. A polymath from the Islamic Golden Age, he wrote hundreds of treatises on alchemy, medicine, astronomy, and engineering. Though some of his works were later exaggerated or falsely attributed, his genuine writings emphasised careful experimentation and record-keeping.

He pioneered techniques such as distillation, crystallisation, and evaporation—methods that remain fundamental in modern laboratories. Western scholars, encountering his symbolic and coded language, mistook him for a magician. But Jabir’s systematic approach and attention to empirical results marked a major step toward modern science.

8. Albertus Magnus (c. 1200–1280)

Albertus Magnus was one of the most respected intellectuals of the medieval world. A Dominican friar, he wrote extensively on subjects like botany, zoology, mineralogy, astronomy, and philosophy. His goal was to reconcile Aristotelian science with Christian theology.

He was said to possess a magical brass head that could speak and answer questions, adding to his mythical reputation. In reality, Albertus was a tireless observer and classifier who tried to understand the natural world on its own terms. His student, Thomas Aquinas, carried on his legacy, and Albertus is now recognised as one of the key thinkers who helped bridge science and religion in medieval Europe.

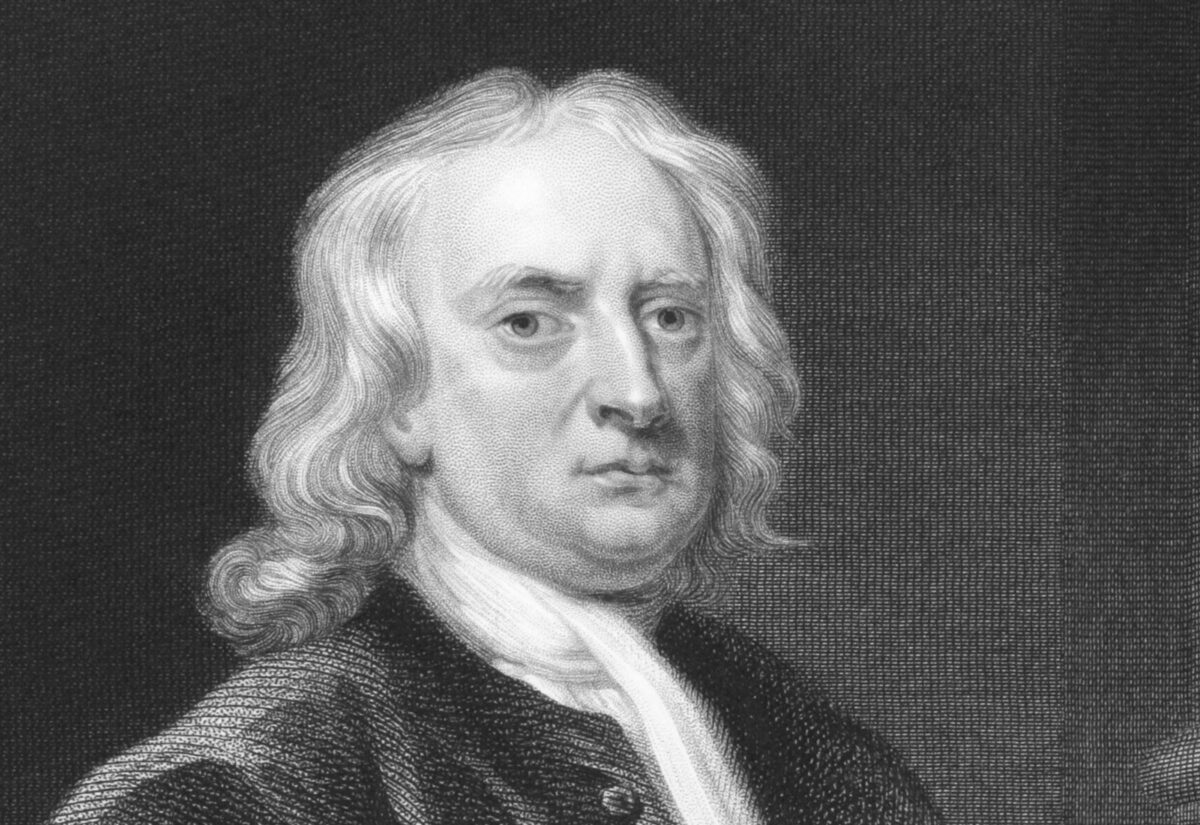

9. Isaac Newton (1643–1727)

One of the greatest minds in history, Isaac Newton revolutionised physics, mathematics, and astronomy. His laws of motion and theory of universal gravitation changed the way we understood the universe. But Newton was also deeply involved in alchemy, Biblical prophecy, and the search for hidden knowledge.

He wrote far more on esoteric topics than on physics, believing there were deeper spiritual truths encoded in scripture and the natural world. Some contemporaries viewed him as secretive or unorthodox. While modern readers focus on his scientific legacy, the full picture of Newton includes a man equally fascinated by the mystical and the measurable.

10. Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 360–415)

Hypatia was a philosopher, mathematician, and astronomer in a time when few women were allowed into public intellectual life. She taught students from across the Roman Empire, edited existing mathematical texts, and made improvements to instruments such as the astrolabe.

Because of her fame and association with pagan philosophy in an increasingly Christianised Alexandria, Hypatia became a target. Smeared as a witch and blamed for political tensions, she was murdered by a Christian mob. Her legacy as a scientist and rational thinker endured despite centuries of myth and suppression. Today, she’s recognised not only as a martyr for science but as a symbol of intellectual integrity.

These historical figures lived in worlds that were often hostile to new ideas. Their work blurred the lines between science, magic, philosophy, and religion—not because they were confused, but because the modern categories didn’t exist yet. They weren’t wizards. They were seekers of knowledge, pushing at the edges of what was known, and laying the foundations for science as we know it today.