Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphotoHistory is full of names that have become shorthand for cruelty, treachery, or evil. But as any good historian knows, context matters—and so does who’s telling the story. The label of “villain” is often handed down by the victors, and many historical figures remembered as monstrous may actually have been far more complex. Some were scapegoated. Others made decisions that, while harsh, were common practice in their time. And some were victims of character assassination, punished more by political propaganda than by any objective standard of morality. Here are 13 historical figures long considered villains who may have been deeply misunderstood—or at least far more human than their reputations suggest.

Richard III (England)

Thanks largely to Shakespeare’s dramatic portrayal, Richard III is remembered as a scheming, murderous hunchback who usurped the throne and murdered his nephews—the infamous Princes in the Tower. But there’s no definitive proof he was responsible for their deaths, and his physical deformity was likely exaggerated for effect.

Historians have since re-evaluated his reign, noting his support for legal reforms and efforts to curb corruption. He introduced protections for landowners, made the legal system more accessible to ordinary people, and was reportedly popular in the north. Richard’s legacy was largely shaped by the Tudors, who needed to discredit him to validate Henry VII’s claim. The truth may be less villainous—and more political.

Empress Wu Zetian (China)

China’s only ruling empress, Wu Zetian has long been portrayed as a cruel usurper who manipulated and murdered her way to power. She certainly consolidated authority with force—but no more so than many male rulers before her.

She was also a capable leader who strengthened the central government, promoted education, and expanded the empire’s influence. She introduced meritocratic reforms and championed Buddhism at a time when Confucian ideals opposed women in power. Much of her negative portrayal can be traced back to Confucian historians who disapproved of a woman holding supreme authority.

Vlad the Impaler (Wallachia)

Vlad III of Wallachia, also known as Vlad the Impaler, inspired the Dracula legend and is infamous for his gruesome method of execution. Yet, in Romania and other parts of Eastern Europe, he’s remembered as a hero who fiercely defended his homeland against Ottoman invasion.

While his punishments were brutal, they were directed at enemies, traitors, and invaders in an age where cruelty was standard fare in warfare. The Western narrative of him as a bloodthirsty monster may have more to do with sensational accounts and xenophobic storytelling than historical fact.

Marie Antoinette (France)

“Let them eat cake”—a quote falsely attributed to Marie Antoinette—has come to symbolise aristocratic apathy. In reality, there’s no evidence she ever said it. She was married to Louis XVI at a young age and had limited influence over the government.

Much of the animosity towards her stemmed from her foreign origins, her lavish lifestyle during a time of national hardship, and the political turmoil of the French Revolution. She became an easy scapegoat for France’s problems. In her final days, she endured personal loss, public humiliation, and execution with dignity.

Boudica (Britain)

To Roman historians, Boudica was a savage leader who burned cities and slaughtered civilians. But to modern British perspectives, she’s a symbol of resistance against imperial oppression. After Roman soldiers flogged her and assaulted her daughters, Boudica led a rebellion against Roman rule.

Her uprising was ultimately unsuccessful and brutally suppressed. However, her story has endured because it represents defiance, resilience, and the fury of someone with nothing left to lose. The Roman accounts that survive were never going to treat her sympathetically—they saw her as a threat to their empire.

Caligula (Rome)

Ancient accounts describe Caligula as an unhinged despot who indulged in cruelty, incest, and delusions of godhood. But these stories often came from senatorial writers hostile to his populist leanings and personal style of rule.

He did alienate the elite, but some historians suggest much of the reputation for madness stems from political smear campaigns. He enacted popular policies, including tax reform and public games, and his strange behaviour may have followed a serious illness early in his reign. The truth likely lies somewhere between reformer and madman.

Genghis Khan (Mongol Empire)

To much of the Western world, Genghis Khan is the embodiment of brutal conquest. But in Central Asia, he’s remembered as a visionary leader who unified fractured tribes, introduced a written script, and laid the groundwork for the largest contiguous empire in history.

He created a law code, promoted religious tolerance, and fostered international trade. Yes, his military campaigns were devastating—but they were not uniquely so for the era. His administrative genius and long-term impact on Eurasian connectivity often get overlooked in favour of tales of bloodshed.

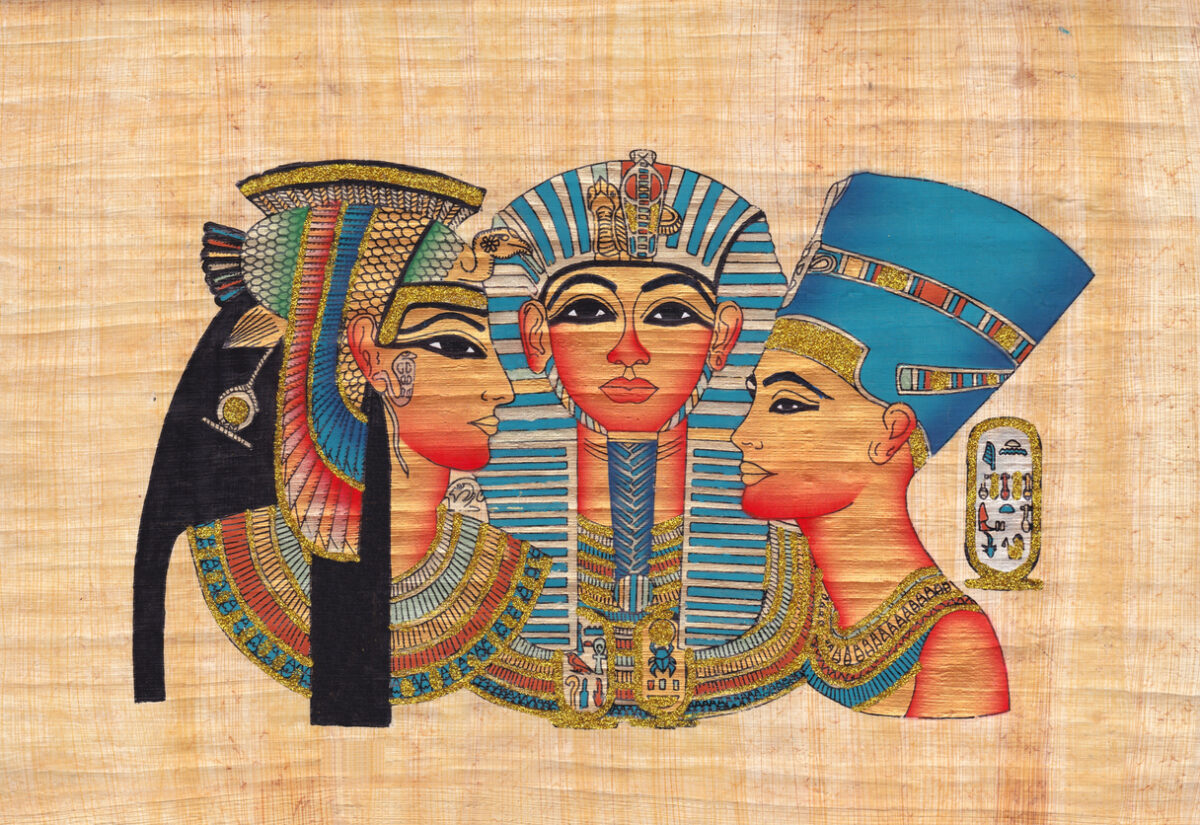

Cleopatra VII (Egypt)

Often cast as a temptress who seduced Julius Caesar and Mark Antony, Cleopatra’s image has been shaped by Roman political spin and later Western fascination with her love life. In reality, she was an astute ruler who stabilised a declining kingdom.

She spoke multiple languages, studied science and philosophy, and actively governed her realm. Roman propaganda, especially under Augustus, painted her as a foreign threat to justify the conquest of Egypt. Her relationships were political as much as personal, and her intellect was central to her power.

Thomas Cromwell (England)

Seen by many as the brains behind Henry VIII’s tyranny, Cromwell’s legacy is often framed through the lens of executions and religious upheaval. But he was also a reformer who helped centralise power, improve administrative efficiency, and modernise the legal system.

He pushed for English translations of the Bible and sought to reduce corruption in the Church. His fall came when he overreached—promoting a marriage Henry hated—and his enemies at court seized the chance to bring him down. His pragmatic, sometimes cold manner earned him few friends—but he was instrumental in reshaping England.

Catherine the Great (Russia)

Catherine II is often remembered for palace intrigue, extravagant tastes, and rumours about her private life. But she was one of Russia’s most effective and forward-thinking rulers, bringing Enlightenment ideas to a largely feudal society.

She expanded Russia’s territory, improved education, founded hospitals, and supported literature and the arts. She corresponded with major philosophers and tried (unsuccessfully) to reform serfdom. Much of her vilification stems from misogyny—male rulers were seldom judged for personal indiscretions with the same intensity.

Attila the Hun

To the Roman Empire, Attila was the ultimate barbarian. He led devastating campaigns across Europe, exacted massive tributes, and was feared for his ruthless tactics. But his own people saw him as a unifier and a powerful leader.

The Huns left few written records, so most of what we know comes from hostile sources. While he did commit acts of brutality, they were not exceptional by the standards of the time. His infamy may be more a matter of Roman fear than historical accuracy.

Niccolò Machiavelli (Italy)

Machiavelli’s name is now synonymous with manipulation and cruelty, thanks to his work “The Prince.” But in reality, he was a civil servant who wanted to understand how power actually functioned—not how it should in an ideal world.

His writings were grounded in the brutal political realities of Renaissance Italy. In other works, he championed republican values and civic responsibility. “The Prince” may even have been satire or a job application gone wrong. He wasn’t advocating villainy—he was trying to explain survival.

Qin Shi Huang (China)

The first emperor of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang is often remembered as a tyrant who burned books, buried scholars, and ruled with an iron fist. But his centralisation efforts standardised language, currency, weights, and infrastructure in a way that laid the foundations for Chinese civilisation.

He built roads, walls, and a central bureaucracy. His tomb complex and the Terracotta Army reflect not just vanity, but a vision of unity and permanence. His reign was harsh, but it marked a turning point in Chinese history—transforming warring states into a single empire.

History is rarely black and white. These so-called villains often walked a fine line between ambition and brutality, reform and repression. In many cases, their reputations have been shaped by biased chroniclers, cultural enemies, or political necessity. Re-examining their lives doesn’t excuse cruelty—but it does add depth. It reminds us that every figure has a human story behind the myth—and that the truth is often more complex than legend.