Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphotoIt’s easy to see disasters as nothing more than destructive, heartbreaking moments—times when entire communities are upended and life becomes defined by loss. But history has a way of flipping the script. While tragedies never come without cost, they’ve often acted as catalysts for change. In the wake of devastation, people have been forced to think creatively, act urgently, and challenge existing systems. Many of the things we take for granted today—whether in public health, engineering, safety, or social policy—were born out of crisis. Here’s a look at some of the most powerful examples where disaster became the unlikely driver of progress.

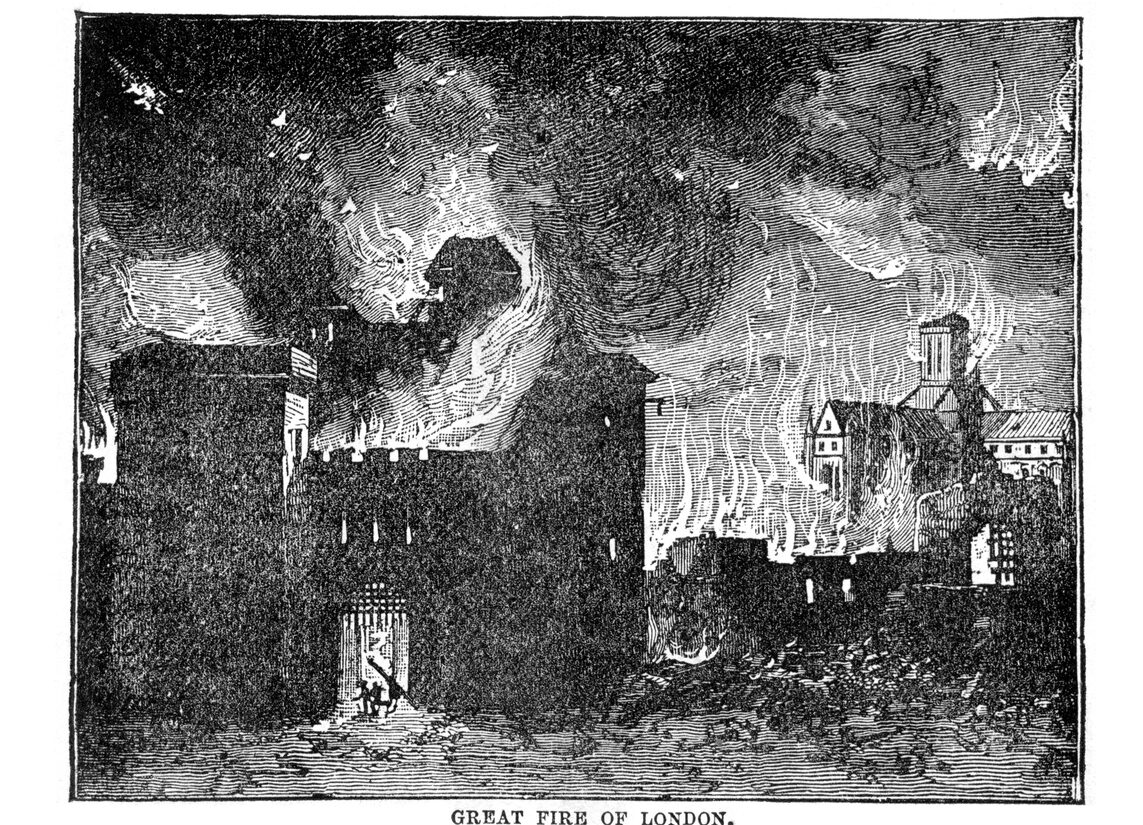

The Great Fire of London (1666)

When fire tore through the heart of London in September 1666, it left an enormous scar. Over four days, around 13,000 homes, 87 churches, and key parts of the medieval city were reduced to ash. But the fire also became a turning point in urban development and public safety. It exposed just how vulnerable the city was, with its narrow alleys, densely packed timber houses, and lack of coordinated emergency services. In the aftermath, Parliament passed new building regulations: homes had to be built using brick or stone, streets were widened to stop future blazes from spreading, and early fire insurance schemes began to appear. It also sparked the beginnings of what would become the modern fire brigade. Architect Christopher Wren proposed an ambitious redesign of the city, including wide boulevards and organised street grids, some of which were implemented, laying the foundation for a safer, more structured London.

The Black Death (14th century)

The plague that ravaged Europe in the 1300s was one of the deadliest events in human history. It’s estimated that between 30 and 60 percent of Europe’s population died. The impact was cataclysmic, but it also dismantled the social and economic structures that had kept people in place for centuries. The dramatic drop in population led to severe labour shortages, empowering peasants and tradespeople to demand better wages and living conditions. In many areas, the feudal system began to collapse. This paved the way for more fluid social mobility and, in time, a stronger middle class. Cities began to implement public sanitation measures and rudimentary quarantine laws, laying the groundwork for future public health infrastructure. The disaster didn’t just reshape population numbers. It reshaped the entire landscape of European society and governance.

The Titanic disaster (1912)

When the RMS Titanic struck an iceberg and sank in April 1912, it became one of the most infamous maritime tragedies in history. The ship, deemed “unsinkable,” lacked enough lifeboats for all passengers, and communication between ships was patchy at best. More than 1,500 lives were lost, but the outcry led to swift and sweeping reform. Governments and maritime organisations responded with urgency, creating new rules that fundamentally changed sea travel. All ships were now required to carry lifeboats for every person on board. Mandatory lifeboat drills and 24-hour radio watches became standard practice. The International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was signed in 1914 and remains one of the most influential maritime safety agreements ever established.

The Aberfan disaster (1966)

In the small Welsh village of Aberfan, a coal spoil tip—an enormous mound of mining waste—collapsed after days of heavy rain, engulfing a school and nearby houses. The landslide killed 144 people, including 116 children. The disaster wasn’t just a freak accident; it was the result of ignored warnings and systemic neglect by the National Coal Board. The outpouring of grief and anger led to major changes in how industrial waste was handled in the UK. It prompted new laws around the monitoring of spoil tips and placed legal responsibility on companies for the safety of their environmental practices. The tragedy also changed the tone of public accountability in Britain. It became a moment when ordinary people demanded transparency, reform, and respect from corporate and government institutions.

The Spanish flu pandemic (1918–1919)

The Spanish flu infected a third of the world’s population and killed tens of millions, more than the First World War that had just ended. It overwhelmed hospitals and exposed just how unprepared the world was for a global health crisis. But out of the devastation came lasting changes. Governments began to understand the need for centralised, coordinated public health systems. It accelerated the establishment of national health ministries and laid the early groundwork for organisations like the World Health Organization. There was also a noticeable shift in how disease prevention was approached. Public information campaigns, hygiene education, and early forms of contact tracing began to emerge. The experience also changed medical research, encouraging collaboration and speeding up the study of virology and immunology.

The Great Smog of London (1952)

In December 1952, a deadly fog descended on London. It was a toxic mixture of coal smoke and stagnant winter air, and it lasted for five days. By the time it cleared, as many as 12,000 people had died from respiratory illnesses. Until then, poor air quality had been tolerated as a grim but normal part of city life. The Great Smog made it impossible to ignore. Public health experts and politicians were forced to act. The Clean Air Act of 1956 was introduced to phase out the use of coal in urban areas, promote cleaner energy sources, and reduce industrial emissions. It marked a major step forward in environmental legislation and sparked the beginning of modern air quality monitoring in the UK.

The Chernobyl disaster (1986)

The explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Soviet Ukraine was one of the most serious man-made disasters in history. It exposed serious flaws in reactor design, emergency planning, and government transparency. But it also forced the global scientific community to work together to better understand nuclear safety. International cooperation increased, and nuclear regulatory bodies became more robust. The disaster led to the development of improved reactor safety protocols, better containment systems, and early-warning radiation detection networks. In many countries, it also triggered broader discussions about energy policy and led to a shift towards renewables.

Hurricane Katrina (2005)

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast of the United States, it exposed deep failures in disaster response, infrastructure planning, and social inequality. New Orleans’ levees failed, thousands were displaced, and the federal response was widely criticised. In the aftermath, it became clear that emergency services were under-resourced and poorly coordinated. Reforms followed. FEMA (the Federal Emergency Management Agency) underwent restructuring, and cities began to invest more heavily in disaster preparedness, early-warning systems, and urban resilience planning. The event also sparked a renewed focus on climate change and the vulnerability of coastal cities.

Disasters are devastating.

They cause pain, suffering, and upheaval, but they also force societies to look closely at what’s broken and find ways to fix it. Whether it’s safer buildings, better health systems, cleaner air, or fairer laws, the innovations that emerge from disaster often shape the world in ways that benefit future generations. These moments in history remind us that resilience isn’t just about surviving. It’s about learning, improving, and never settling for systems that fail the people they’re meant to protect.