Getty Images/iStockphoto

Getty Images/iStockphotoAt its height, the British Empire was the largest in history, stretching across nearly a quarter of the globe and affecting the lives of millions. It brought with it railways, bureaucracies, and trade routes, but also exploitation, dispossession, and fierce resistance. While many regions were absorbed into its sprawling control, some managed to fight back, either avoiding conquest entirely or resisting it to such an extent that British control remained superficial or temporary. Whether through military strength, geographic isolation, diplomatic manoeuvring, or unyielding cultural resilience, these regions and peoples challenged the assumptions of imperial dominance. Here are some of the most striking examples of places that Britain could never fully control.

1. Afghanistan

Afghanistan was never officially colonised by Britain, though not for lack of effort. The British invaded three times during the 19th and early 20th centuries, determined to create a compliant buffer state that would keep Russian influence at bay. The First Anglo-Afghan War (1839–1842) was a disaster for the British, ending with the near-total annihilation of their retreating army during a catastrophic retreat from Kabul.

Despite temporary occupations and puppet leaders, the British failed to establish sustained control. The Second Anglo-Afghan War saw similar short-term gains but long-term frustration, and by the time of the Third War in 1919, Afghanistan had regained control of its foreign policy and asserted full independence. The National Army Museum provides a comprehensive look into these turbulent episodes.

2. Ethiopia

Unlike much of Africa, Ethiopia retained its sovereignty throughout the colonial period, withstanding both Italian and British interference. While Britain never tried to colonise Ethiopia in the traditional sense, it did launch a military campaign in 1868 against Emperor Tewodros II, primarily to free British hostages.

The military campaign was successful, but it was short-lived. After Tewodros’ suicide, British troops withdrew. Later, during World War II, Britain temporarily occupied Ethiopia to help expel the Italian invaders. However, British forces left in 1944, and Ethiopia maintained its independence, becoming a symbol of African resistance to European imperialism.

3. Nepal

The mountainous kingdom of Nepal fiercely defended its autonomy during the Anglo-Nepalese War of 1814–1816. Though the war ended in the Treaty of Sugauli, with Nepal ceding significant territory, the kingdom retained its sovereignty and internal governance.

The British, impressed by the military prowess of the Gurkhas, began recruiting them into their army, forging a unique relationship that persists to this day. Nepal became a buffer state between British India and Qing China but never lost its monarchy or domestic authority. This balance of military respect and diplomatic necessity kept Nepal out of colonial hands.

4. Bhutan

Bhutan, like Nepal, managed to avoid full colonisation despite British attempts to exert control. The Duar War (1864–1865) resulted in the Treaty of Sinchula, which saw Bhutan lose some territory but retain internal autonomy.

Bhutan became a British protectorate, meaning Britain managed its foreign affairs but not its domestic governance. The mountainous terrain and the kingdom’s deliberate isolationist policies made deeper incursions difficult. Bhutan would later transition from a monarchy to a constitutional democracy, but on its own terms.

5. Ireland

Although Ireland was formally part of the United Kingdom, the relationship bore all the hallmarks of colonialism: dispossession, cultural suppression, forced emigration, and economic control. From the Tudor conquests to the Great Famine and beyond, Ireland experienced centuries of resistance to British authority.

The 1916 Easter Rising, followed by the War of Independence (1919–1921), ultimately led to the creation of the Irish Free State in 1922. While Northern Ireland remained under British control, the rest of the island broke free. The story of Ireland’s resistance is both long and bitter, but ultimately it marked a rare instance of a British “home territory” achieving self-rule through sustained internal struggle. RTÉ Archives explores this pivotal moment in Irish history.

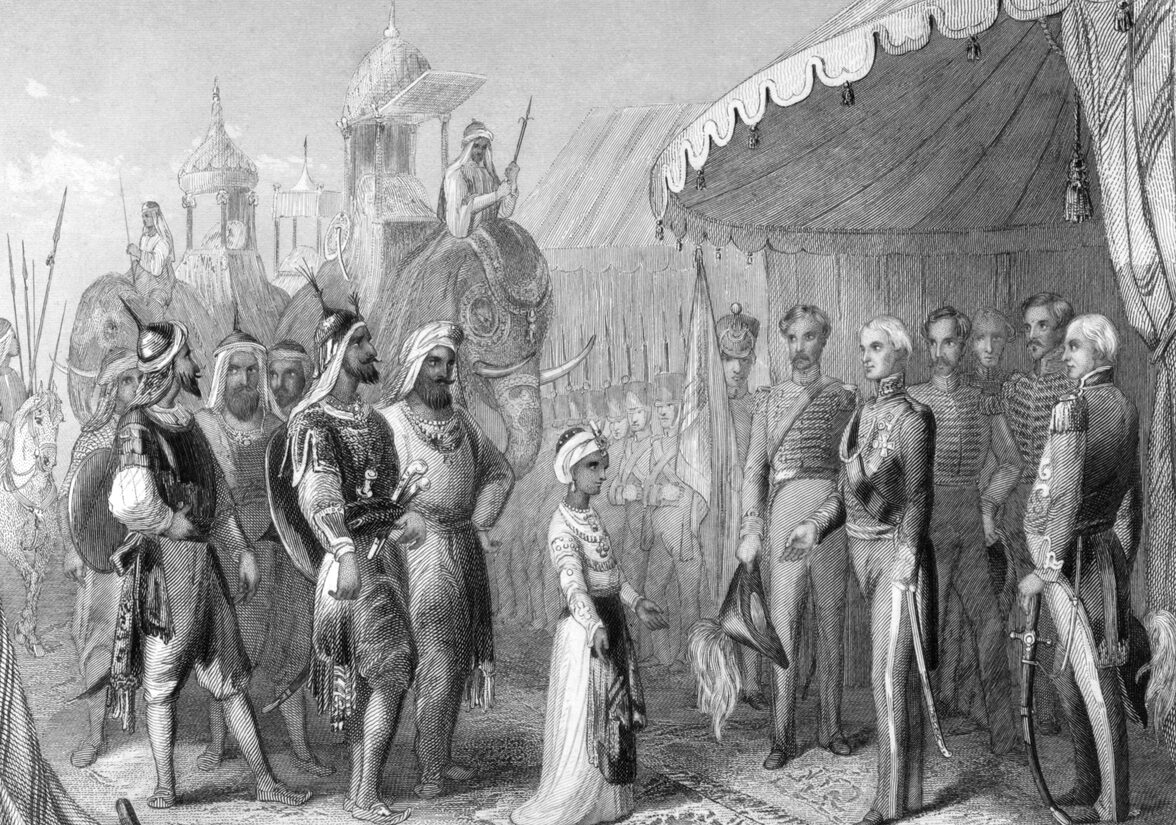

6. The Maratha Confederacy (India)

Before the British gained full control of the Indian subcontinent, the Maratha Empire posed one of the most formidable obstacles. From the early 18th century through to their defeat in 1818, the Marathas engaged the British in a series of conflicts known as the Anglo-Maratha Wars.

Even after their eventual defeat, the Maratha resistance delayed British expansion for decades and forced the East India Company to invest heavily in military and diplomatic resources. Their decentralised power structure made them hard to dismantle quickly, and their prolonged defiance shaped the trajectory of British imperialism in India.

7. Somaliland (British Somaliland)

British control over Somaliland was never as deep as in other colonies. The coastal areas were more accessible and easier to manage, but the interior was fiercely defended, particularly by the Dervish State led by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan.

From 1899 to 1920, Hassan’s forces waged a guerrilla campaign against the British, resisting multiple military campaigns. In 1920, the British resorted to aerial bombardment—the first of its kind in Africa—to suppress the rebellion. Even then, control remained limited until the region merged with Italian Somaliland to form modern-day Somalia in 1960.

8. The Ashanti Empire (Gold Coast)

In present-day Ghana, the Ashanti Empire resisted British colonisation across five wars spanning from 1824 to 1900. The Ashanti maintained a sophisticated military, political structure, and trade network that proved resilient in the face of imperial aggression.

Though Kumasi was eventually captured and the Ashanti kingdom formally annexed, resistance continued, and British control remained shaky. Ashanti cultural institutions survived, and to this day, the Ashanti King holds an influential traditional role in Ghanaian society.

9. Tibet

Tibet’s strategic location between India and China made it a target of British interest. In 1903–1904, the British launched an expedition led by Colonel Francis Younghusband, resulting in a violent incursion into Lhasa. The goal was to secure trade and pre-empt Russian influence.

Although the British succeeded in securing treaties, they failed to establish long-term control. Tibet remained largely autonomous until Chinese occupation in the 1950s. The British retreated, realising the region’s remoteness and resistance made it a poor candidate for colonisation.

10. Sikkim

Sikkim, a small Himalayan kingdom, became a British protectorate but was never directly ruled. The British wanted control over the trade routes between India and Tibet and used diplomacy, treaties, and strategic alliances to influence Sikkim’s foreign affairs.

While Britain did gain influence, the internal governance of Sikkim remained largely in the hands of its Chogyal (monarch). Sikkim would eventually become part of India in 1975, but during the imperial era, it managed to retain a measure of self-rule.

11. Yemen (South Arabia)

The British established a base in Aden in the 19th century, but their attempts to extend control inland into Yemen were largely unsuccessful. The rugged terrain, strong tribal alliances, and constant resistance kept the interior largely autonomous.

While Britain held onto Aden until 1967, the surrounding regions were only nominally under imperial control. Resistance movements, including nationalist and Marxist groups, eventually pushed the British out, making South Yemen the only Arab Marxist state after independence.

The narrative of empire is often told from the perspective of dominance and control, but these stories tell a different side.

Whether through military resistance, diplomatic skill, cultural resilience, or sheer geographical advantage, many regions resisted British rule in ways that shaped their futures, and Britain’s. Some were never conquered, others were only partially controlled, and still others reclaimed their autonomy through persistent struggle.

Recognising these histories doesn’t diminish the scale of British imperialism, but it adds much-needed complexity. Empire was never monolithic. It was always contested, and these examples show just how many people refused to be ruled quietly. Their stories are vital to understanding not just the past, but the enduring legacies of resistance that shape the world today.