Ancient Social Classes That Have No Modern Equivalent

- Jennifer Still

- May 23, 2025

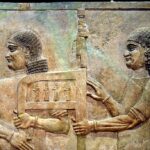

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0

Osama Shukir Muhammed Amin FRCP(Glasg), CC BY-SA 4.0In ancient societies, the concept of class wasn’t just about wealth or status—it was often bound up with religion, heredity, ethnic identity, and civic duty in ways that no longer translate easily into our current frameworks. These weren’t fluid social standings that you could climb out of with the right education or income—they were fixed roles that often lasted a lifetime, if not generations. Some existed to uphold ritual or military systems, others to maintain economic control, and many were deeply embedded in a civilisation’s very sense of order. Here are some of the most unique social classes from antiquity that simply don’t exist in any comparable form today.

Eunuchs in imperial courts

In several ancient empires—including China, Byzantium, and the Ottoman Empire—eunuchs were given access to power and proximity that most men couldn’t dream of. Castrated as boys, often under coercive or brutal conditions, eunuchs were considered safe to serve in intimate royal roles because they were seen as lacking family ambitions.

In some cases, eunuchs rose to extraordinary levels of influence. In Ming China, Zheng He, a eunuch, commanded massive naval expeditions that travelled as far as the coast of Africa. Byzantine eunuchs often held high-ranking military or administrative posts, and in the Ottoman Empire, they controlled access to the sultan and managed the harem. Their position wasn’t merely symbolic—it was embedded in how these courts functioned. There is no modern social class based on both a surgical procedure and lifelong institutional loyalty.

Spartiates of ancient Sparta

The Spartiates were the full citizens of Sparta—a tiny minority with enormous privilege and extreme responsibilities. From the age of seven, boys were taken from their families and enrolled in the agoge, a brutal state-run education system designed to create the perfect warrior. They were forbidden from engaging in manual labour, trade, or farming—those roles were left to others. A Spartiate’s life was exclusively devoted to military readiness and the state.

Unlike modern professional soldiers, their entire identity and citizenship were rooted in warfare. Even leisure was structured around preparation for combat. In today’s world, where military service is often voluntary and comes with time limits, the idea of a permanent warrior class tied to birth and state ideology feels entirely foreign.

Helots in Spartan society

Sparta’s military elite relied entirely on the helots—a vast population of state-owned serfs tied to the land. These weren’t slaves in the usual chattel sense, but they weren’t free either. Helots lived in family units and maintained a degree of community life, but they were forced to farm and surrender a portion of their produce to their Spartan overlords.

Every year, Sparta declared ritual war on the helots, allowing their murder without legal consequence. This was not just a matter of control—it was ideological. It ensured a sense of permanent submission, enforced by institutionalised fear. Modern systems of labour and class oppression may echo aspects of this, but the sheer codified brutality and state-sanctioned violence against an internal labouring population have no equivalent today.

The Brahmins of Vedic India

Brahmins, at the top of the early Hindu varna system, were seen not merely as religious figures, but as stewards of cosmic and moral order. Their responsibilities ranged from preserving sacred texts and conducting elaborate rituals to advising kings. Their knowledge of Sanskrit and the Vedas gave them unmatched authority in intellectual and spiritual life.

What set the Brahmins apart was their integration into every part of society—from law and politics to education and domestic rituals. Their role wasn’t something one could study for or aspire to—it was inherited, protected by religious law, and deeply respected (and sometimes resented). While religious scholars still exist, the total institutional authority and divine prestige once held by Brahmins in early Vedic society has no true modern comparison.

Roman freedmen

In Rome, a freed slave didn’t become just an ordinary citizen—they entered a unique in-between class. Freedmen could earn and own property, run businesses, and even become wealthy, but they couldn’t hold major public office. They remained socially distinct from freeborn citizens.

Many retained obligations to their former masters, now called patrons, creating a bond that shaped their legal and social position. Some freedmen, especially in the imperial household, became extremely powerful—running bureaucracies and managing elite affairs. Today’s class systems may recognise former prisoner status or economic mobility, but the specific limbo of freedmen as a formalised post-slavery class tied to patronage doesn’t exist anymore.

Plebeians and patricians in Rome

The distinction between plebeians and patricians was about lineage, not wealth. Patricians claimed descent from Rome’s original aristocratic families, and for centuries, held exclusive access to the Senate, priesthoods, and high office. Plebeians, regardless of financial success, were shut out.

The divide softened over time, but it shaped centuries of Roman law and politics. Today’s social elites are often based on money, education, or inherited wealth—but rarely on state-backed ancestral privilege protected by law.

Metics of Athens

Metics were foreigners allowed to live in Athens but denied citizenship. They paid taxes, fought in wars, and contributed to trade and culture—but could never vote, own land, or marry citizens without special permission.

Their existence created a dependent class: vital to the economy but permanently excluded from political life. While echoes of this exist in debates over migration and legal status today, few modern democracies formally define a lifelong, contribution-based second-class residency in quite the same way.

Egyptian temple priesthoods

Ancient Egypt’s priesthoods weren’t just religious—they were economic and bureaucratic powerhouses. Temples owned land, stored grain, employed artisans, and educated scribes. Priests managed these vast estates while also conducting daily rituals to maintain divine favour.

Often hereditary, priestly roles were both spiritual and managerial, deeply enmeshed in the machinery of state. Few modern religious institutions today function as government-adjacent corporations, blending mysticism and logistics at such scale.

The Mamluks

Mamluks were enslaved boys, often from Central Asia or the Caucasus, brought to Islamic states—especially Egypt—and trained as elite soldiers. Unlike typical slave soldiers, the Mamluks rose to form their own military caste and eventually took control of Egypt, ruling as independent sultans from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries.

They were both outsiders and rulers, denied personal freedom but granted supreme authority. This paradox of a ruling slave aristocracy has no real modern counterpart. Their entire identity was forged through a unique system of bondage, training, and political ascent.

The hoplites of ancient Greece

Hoplites were middle-class citizens who could afford their own armour and weapons. Their participation in the phalanx—an infantry formation requiring trust and discipline—was both a military duty and a civic credential.

Serving as a hoplite was tied to land ownership and voting rights, linking military service directly to democracy in cities like Athens. Today, military service and political participation are no longer bound in this way. The idea that only those who risk their lives in battle can have a voice in government has faded in most societies.

The Pharaoh as divine ruler

In ancient Egypt, the pharaoh was more than a king—he was a living god. His role wasn’t just political; it was cosmological. The pharaoh mediated between the divine and human worlds, ensuring the sun rose, the Nile flooded, and the cosmic order (ma’at) was maintained.

This divine kingship granted him a unique status that no president, monarch, or prime minister can claim today. Even in societies with strong monarchies, there is usually a clear distinction between the human and the divine—a line ancient Egyptians did not draw.