Unsplash/National Archief

Unsplash/National ArchiefHistory tends to focus on the winners, but some of the most fascinating political moments come from movements that didn’t quite make it—those that came tantalisingly close to reshaping British politics, society, or even the monarchy, but ultimately fell short. Many of these campaigns weren’t minor footnotes or fringe outbursts either. Some had mass support, influential backers, and concrete legislative proposals. While none of them achieved their ultimate aims, all of them left a mark that rippled forward through the decades. Here are some of the most compelling British political movements that nearly rewrote the rulebook.

1. The Levellers (1640s–1650s)

In the wake of the English Civil War, the Levellers emerged as one of the most radical and articulate political groups of the 17th century. With a platform that included universal male suffrage, equality before the law, religious tolerance, and the abolition of monopolies, they were far ahead of their time.

Their influence peaked around 1647, when their ideas were widely debated among soldiers in the New Model Army. The famous Putney Debates laid bare the divide between those who wanted moderate reform and those, like Leveller spokesman Thomas Rainsborough, who insisted that every man, rich or poor, deserved a political voice. Their power unnerved Cromwell and the ruling elite. The army’s mutinous regiments were violently suppressed, key leaders like John Lilburne were jailed, and the movement collapsed. But the Levellers’ vision endured, influencing 18th- and 19th-century reformers.

2. The Chartist Movement (1838–1857)

Industrialisation brought immense wealth to Britain, but it also produced deep misery, especially for the working classes. In this climate, the Chartists launched a campaign for democratic reform, centred around the People’s Charter of 1838. Their six key demands included universal male suffrage, a secret ballot, and salaries for MPs.

Millions supported them, and three huge petitions were presented to Parliament—in 1839, 1842, and 1848. The final petition claimed over six million signatures, though this figure is still debated. Despite mass meetings and marches, Parliament refused to act. The movement faded by the 1850s, but five of its six demands were later adopted. The British Library has extensive records showing how influential the Chartists became.

3. The Jacobite Risings (1688–1746)

The Glorious Revolution of 1688, which ousted the Catholic James II in favour of his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange, sparked over half a century of unrest. The Jacobites, supporters of James and his descendants, fought to restore the Stuarts to the throne.

The most serious threat came in 1745, when Charles Edward Stuart (“Bonnie Prince Charlie”) landed in Scotland and marched his army into England. For a time, it looked like they might succeed. Manchester welcomed them, and they got as far south as Derby. But poor strategic decisions and a lack of English support led to retreat. The final defeat at the Battle of Culloden in 1746 crushed the movement militarily, but its romanticism endured in Highland culture and lore.

4. Suffragette Militancy (1903–1914)

While women’s suffrage was a long campaign, the militant phase led by Emmeline Pankhurst and the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) nearly forced the government into early concessions. The WSPU broke with peaceful campaigners by using tactics like window-smashing, hunger strikes, and chaining themselves to public buildings.

The state’s response was harsh—arrests, force-feeding, and widespread surveillance. But the publicity generated was impossible to ignore. By 1914, the suffragettes had become a serious political force. The outbreak of World War I paused the militancy, but the war itself boosted the case for women’s votes, leading to partial enfranchisement in 1918 and full equality in 1928.

5. The General Strike of 1926

The post-World War I economy was turbulent, and Britain’s coal industry was in crisis. When mine owners proposed wage cuts and longer hours, the Trades Union Congress called a general strike in solidarity. For nine intense days in May 1926, railway workers, dockers, printers, and others walked off the job.

Although essential services were kept running with the help of volunteers, the disruption was significant. The government used propaganda, emergency powers, and even the army to maintain order. Eventually, the TUC called off the strike without securing any victories for miners. Despite the failure, it was a landmark in British labour history, prompting anti-union legislation and igniting debates that would stretch well into the 20th century. The National Archives holds fascinating original materials from the time.

6. The SDP–Liberal Alliance (1981–1988)

Frustrated by the hard-left direction of Labour in the early 1980s, a group of centrist MPs—including Roy Jenkins, Shirley Williams, David Owen, and Bill Rodgers—formed the Social Democratic Party (SDP). They quickly allied with the Liberal Party, hoping to establish a credible centrist challenge.

Their best shot came in the 1983 general election. Despite winning over 25% of the vote nationally, Britain’s first-past-the-post system translated that into just 23 seats. The momentum fizzled out, but the movement permanently shifted British political discourse. The Liberal Democrats, formed from the eventual merger of the SDP and Liberals, remain a fixture in UK politics.

7. Scottish Independence Referendum (2014)

In September 2014, Scotland held its first ever independence referendum, posing the question: should Scotland be an independent country? Turnout was unprecedented at nearly 85%, and the vote ended 55% against, 45% in favour.

But the “Yes” campaign came remarkably close. For a few days in the final stretch, polls showed a possible lead for independence. The result did not end the issue. In fact, the referendum galvanised Scottish nationalism, helped the SNP dominate Scottish politics, and laid the groundwork for future calls for another vote, especially in the wake of Brexit, which most Scots opposed.

8. The Peasants’ Revolt (1381)

Triggered by a hated poll tax and long-standing economic grievances, the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 was unprecedented in scale and coordination. Led by Wat Tyler, thousands of peasants, artisans, and labourers marched on London, burning symbols of aristocratic power and demanding reforms.

Amazingly, they captured the Tower of London and executed several high-ranking officials. King Richard II met with the rebels and seemed to agree to their demands. However, once Tyler was killed, either by accident or design, the rebellion collapsed. Although short-lived, the revolt sent shockwaves through the ruling class and contributed to the eventual decline of serfdom in England.

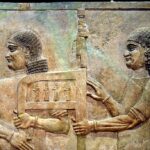

9. The English Republican Movement (1649–1660)

Following the trial and execution of King Charles I in 1649, England became a republic known as the Commonwealth. Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector, and for over a decade, the monarchy was abolished.

Though the republic had military strength, it lacked broad public legitimacy. Cromwell’s regime became increasingly autocratic, and after his death in 1658, the experiment unravelled quickly. In 1660, Charles II was restored to the throne. Still, the decade of republicanism demonstrated that Britain could, at least temporarily, exist without a monarch—an idea that seemed unthinkable just years earlier.

10. The British Union of Fascists (1932–1940)

Led by Oswald Mosley, the British Union of Fascists (BUF) sought to capitalise on economic frustration during the 1930s. With its blackshirt uniforms, paramilitary rallies, and authoritarian rhetoric, the BUF gained significant attention, and briefly, significant support.

At its peak, it claimed over 50,000 members and held packed rallies, including the infamous 1934 Olympia meeting, which ended in violent clashes. Public opinion quickly turned. After the outbreak of World War II, the group was banned, and Mosley was interned. The BUF never posed a serious electoral threat, but it came disturbingly close to shifting Britain’s political climate.

British history is full of movements that nearly changed everything. Some were idealistic, others dangerous, but all had moments where they looked like they might prevail. While these campaigns ultimately fell short, their influence lived on in legislation, culture, and the popular imagination. They remind us that political change rarely happens overnight. Sometimes the most powerful legacy comes not from outright success, but from almost making it.