Indigenous Communities That Have Maintained Traditional Ways Despite Modernisation

- Gail Stewart

- May 22, 2025

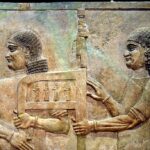

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile much of the world has embraced rapid modernisation, globalisation, and digital connectivity, many Indigenous communities have continued to preserve their traditional cultures, belief systems, languages, and unique ways of life. This isn’t a rejection of change, but often a deliberate, resilient effort to retain cultural identity, protect heritage, and uphold long-standing relationships with the land and ancestors. In many cases, these traditions have survived colonialism, displacement, and systemic attempts at assimilation. These communities have held onto what matters most to them, proving that cultural continuity and adaptation are not mutually exclusive.

The San people (Southern Africa)

Also known as Bushmen, the San are among the oldest continuous cultures on Earth, with archaeological records tracing their existence back tens of thousands of years. Spread across Botswana, Namibia, Angola, and South Africa, their lives have traditionally revolved around nomadic hunting, gathering, and an intricate understanding of the natural world.

San rock art, found throughout southern Africa, reflects their deep spiritual connection to animals and landscapes. Even today, many San elders pass down ancient knowledge of tracking, bushcraft, and traditional medicine. Modern pressures such as land seizures, conservation restrictions, and marginalisation have made this harder, but initiatives led by San people are preserving languages like N|uu and !Kung, and documenting oral histories. Some communities are also working with researchers to integrate traditional ecological knowledge into conservation work.

The Sámi (Northern Europe)

The Sámi are the only Indigenous people officially recognised in the European Union, living across the Arctic regions of Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. Their culture has long centred around reindeer herding, fishing, and crafting, with seasonal migrations being a hallmark of their way of life.

Despite centuries of suppression, including language bans and land encroachments, many Sámi continue to speak their languages, practice joik (a unique form of song), and pass down oral histories. In recent decades, Sámi parliaments have been established in several countries to protect rights and promote cultural autonomy. Modern Sámi artists, educators, and activists are revitalising traditions while challenging state policies that threaten their way of life.

The Yanomami (Amazon rainforest)

The Yanomami people, who live in dense rainforest territories straddling northern Brazil and southern Venezuela, are among the most isolated Indigenous groups in South America. Their communities maintain collective longhouses, rely on slash-and-burn horticulture, hunting, and fishing, and uphold intricate spiritual and shamanic systems.

Despite facing illegal gold mining, deforestation, and disease exposure, the Yanomami have fought to defend their lands. In Brazil, their territory was legally demarcated in the 1990s after years of activism. Organisations like the Instituto Socioambiental and Survival International work alongside the Yanomami to promote health care access and protect their rights. Their shamanic knowledge and sustainable forest management practices continue to influence environmental advocacy globally.

The Ainu (Japan)

The Ainu, Indigenous to Hokkaido in northern Japan, faced centuries of marginalisation and cultural erasure under Japanese rule. Their animist worldview, which holds that gods inhabit all things—plants, animals, rivers—shaped a rich spiritual life including ritual dances, oral epics, and unique crafts.

Though assimilation policies suppressed language and cultural expression for over 100 years, the Ainu have experienced a cultural resurgence since their official recognition in 2019. Community centres like the Upopoy National Ainu Museum promote language revitalisation and traditional arts. Festivals now celebrate Ainu music, storytelling, and cuisine, and younger generations are proudly reclaiming their heritage.

The Inuit (Arctic regions)

The Inuit inhabit the Arctic territories of Canada, Greenland, Alaska, and parts of Russia. Their adaptability to an extreme environment is unmatched: building snow shelters, navigating with celestial and environmental cues, and sustaining themselves through hunting seals, whales, and caribou.

While modern tools have entered their lives—such as GPS, rifles, and powered boats—Inuit communities remain deeply committed to traditional values. Language instruction in schools, revitalisation of throat singing, and land-based learning programmes are just a few ways Inuit heritage is being preserved. The Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami plays a leading role in policy advocacy and cultural protection.

The Maasai (Kenya and Tanzania)

The Maasai of East Africa are known for their striking attire, pastoralist traditions, and community cohesion. Livestock, especially cattle, form the backbone of their economy and spiritual life, and many Maasai continue to follow semi-nomadic patterns across arid savannahs.

Government pressure to settle and adopt modern farming methods has met resistance. Many Maasai elders view these changes as threats to land rights and cultural sovereignty. However, some communities have selectively embraced technology, such as using mobile phones for veterinary care or livestock trade, while still holding on to initiation ceremonies, oral traditions, and communal land management systems.

The Hopi (Southwestern United States)

The Hopi people, living in what is now northern Arizona, have a rich history stretching back over a millennium. Their spiritual practices, based on a complex understanding of harmony with nature, are central to Hopi life.

They still practise dry farming in one of North America’s driest regions, growing drought-resistant crops such as blue corn. The Hopi ceremonial calendar is meticulously maintained, with masked kachina dances and rituals tied to agricultural cycles. While modern housing and education systems exist in their communities, the Hopi have consistently prioritised the preservation of traditional governance, language, and religious life.

The Chukchi (Siberia)

The Chukchi, Indigenous to Russia’s Chukotka Peninsula, are divided into reindeer herders of the inland tundra and marine hunters along the coast. Traditional dwellings like yarangas, dietary reliance on reindeer meat and blubber, and animist spiritual beliefs still characterise their way of life.

During the Soviet era, forced collectivisation and assimilation policies threatened Chukchi cultural continuity. Despite this, many Chukchi maintained their language and customs. Today, local efforts to revive storytelling, Chukchi-language media, and youth herding programmes are helping to rebuild cultural pride and sustain traditions that have endured for millennia.

The Zapatista communities (Mexico)

While not defined solely by ethnicity, the Zapatista movement, largely led by Indigenous Maya groups in Chiapas, Mexico, has created a model of grassroots autonomy rooted in Indigenous identity. Since their uprising in 1994, Zapatista communities have resisted neoliberal development and established their own education, health care, and agricultural systems.

Their governance model is built on consensus, rotation of leadership, and respect for Indigenous traditions. Language revival, traditional farming techniques, and an emphasis on collective land ownership define their approach. Despite external challenges, Zapatistas have shown how traditional principles can inform contemporary resistance and community development.

The Aboriginal communities of Arnhem Land (Australia)

Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory is one of Australia’s most culturally intact Aboriginal regions. The Yolŋu and other language groups maintain deep ties to ancestral lands, guided by a worldview that places spiritual and environmental stewardship at its centre.

Ceremonial law, sacred songlines, bark painting, and kinship systems are actively practised. Many communities participate in ranger programmes that combine traditional land management with modern conservation science. Despite ongoing challenges related to land rights and socio-economic inequality, Arnhem Land remains a stronghold of Aboriginal identity and cultural continuity.

The Batak (Philippines)

The Batak people of Palawan Island are one of the Philippines’ oldest Indigenous groups. Traditionally semi-nomadic, they gather wild honey, rattan, and forest produce, and practise swidden agriculture in harmony with local ecosystems.

Modern development projects and mining have placed intense pressure on Batak lands and livelihoods. Yet, community elders continue to teach oral history, traditional forest navigation, and animist spirituality to younger generations. NGOs and cultural heritage programmes are helping to document endangered practices and languages.

The Mentawai (Indonesia)

Living in the forests of Siberut Island, west of Sumatra, the Mentawai are known for their extensive body tattoos, sharpened teeth, and animist beliefs that centre on harmony with the spirits of nature. Traditional longhouses called “uma” form the basis of social life.

Government policies have attempted to relocate and integrate Mentawai into mainstream Indonesian society, but many have resisted. Tattooing, traditional medicine, and the use of forest plants remain widely practised. Community-led initiatives are now helping preserve cultural heritage, even as some younger Mentawai pursue education and work outside their villages.

Preserving traditional ways of life in the face of modernisation isn’t about resisting the future.

It’s about ensuring that history, culture, and identity remain intact for generations to come. These Indigenous communities show that it’s possible to adapt without losing sight of who you are. Their strength lies not just in holding on, but in evolving on their own terms, blending tradition with innovation in ways that serve their people, their land, and their values. Their stories aren’t relics—they’re living examples of resilience and the power of cultural continuity in a fast-changing world.